Cheatgrass

Bromus tectorum

Class C Noxious Weed

This plant is widespread in the state and has been designated a Class C Noxious Weed by the New Mexico Department of Agriculture.

Read more >>>

Fire Hazard

This plant is documented to negatively impact fire regimes in our region. Its presence can increase the frequency and/or severity of fires.

Read more >>>

Toxic to Horses

This plant has been documented to sicken or injure horses.

Read more >>>

QUICK FACTS

- Cheatgrass (or downy brome) is a non-native grass that displaces native plants and severely degrades New Mexico’s unique ecosystems. It is especially invasive in arid rangelands and is credited with the mass destruction of native sagebrush prairie throughout the Western United States.

- This plant gets its competitive advantage from its winter-annual lifecycle. It germinates through the cold season, taking up all the soil nutrients and snowmelt… making it extremely difficult for other plants to germinate in the spring.

- Cheatgrass also dies very early in the year; it is usually dead by the summer and fall, leaving behing highly flammable tinder during the hottest part of the year. Across the landscape, cheatgrass has severely worsened and intensified fire regimes.

- Animals can graze on cheatgrass early in the year when the vegetation is still green and soft. However, it dies early in the growing season, and the dried up florets become tough and spikey, potentially injuring or even rupturing the digestive organs of horses and livestock.

1. Overview

Across the western United States, this prolific grass has earned the nickname “cheatgrass” among farmers and ranchers for its impressive ability to “cheat” them out of profits.

If you live in the western US, you are as familiar with cheatgrass as you are with the hassle of picking out their sharp, barbed seeds from your clothes and your dog’s fur. Bromus tectorum, commonly named downy brome around the world, is one of the most important crop pests for land managers in the country. Since the early 1800’s cheatgrass has contributed to the degradation of our rangelands, as well as exacerbated fire regimes throughout the west.

History of Cheatgrass

Cheatgrass is native to the Eurasian steppe. It is thought to have traveled in the shadow of herders in those regions, traveling from central Asia and across the Mediterranean. Since then it has traveled all around the globe as a contaminant of crop seeds. In the United States it was first identified in the 1860’s, and today it occurs throughout most of the North American continent, from Greenland to northern Mexico.

It has been particularly destructive in the Great Basin and Intermountain West, which span multiple states, from western Oregon on down to New Mexico. Its seeds stowed away within shipments of legitimate crop seed, and it sneaked its way across the range until overgrazing allowed it to dominate.

In the early 19th century, when ranchers began introducing their livestock to the western rangelands, they quickly realized that irrigable land and water here was too scarce to grow the hay meadows necessary to support cattle through the winter. So they turned them out onto the open land, where their cows feasted on wild rose, willow thickets, and even went to town on the sagebrush. Ranchers relied particularly on native bunchgrasses to fill the hay gap during the winter months, but found that those too were becoming more scarce year after year. In their place, a “mystery” grass began showing up, by the roadside, under the sagebrush, and it provided forage for cattle just when the ranchers needed it most. Cheatgrass grew in the aftermath of the destruction of native vegetation, and at first the ranchers welcomed it, and even sought to plant it themselves. But before they got the chance, they found it had already sprung up spontaneously everywhere they looked

According to the Forest Service, cheatgrass infestations in these regions have increased dramatically over the last 20 years, with some sources indicating over 100 million acres infested and millions of dollars in lost profits. Today, cheatgrass is responsible for human and environmental harm, from the decimation of sagebrush ecosystems, to devastating grassland fires.

2. ID Guide

What does it look like?

Key Features

- Cheatgrass is a tufted bunchgrass, appearing as solitary bunches or more often as a patch. Individual plants usually grow about 4 to 30 inches tall.

- Leaves are flat blades with a sheath surrounding the stems; both the leaf and the sheath are densely covered with thin hairs. The base of the leaf blade has a short “collar” – a short translucent membrane of thin hairs called a ligule.

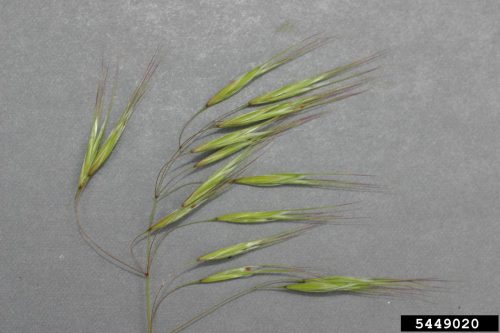

- Flowers: While grasses do not have obvious flowers, you will notice the florets, or flowering tops of cheatgrass are dense and slender. They are arranged in a lose, branching cluster of seedheads called a panicle. These seedheads are about 3-6 inches long and have a characteristic drooping behavior, often found nodding along with the breeze.

- When the plants are young, the foliage is soft and green. As cheatgrass matures, the foliage and especially the seedheads become purplish, and later reddish-brown as it dries up. By the time the plant dies, the foliage is brown or tan and the texture becomes very dry, coarse, and spikey.

Dead cheatgrass turns fully brown or tan; the florets are now very dry and spikey. At this point, it can injure livestock and horses if consumed.

Another example of cheatgrass florets beginning to turn purple.

Young cheatgrass florets; at this point they may be safe and palatable for livestock.

Tips and stems of florests begin to turn purple as the plant matures.

At the end of its life cycle, cheatgrass plant has turned brownish-red and is no longer good forage.

Fully dead cheatgrass florets can injure the throats and digestive tracts of animals

detailed flower info

Cheatgrass stems begin to turn red as the plant mature; note the thin white collar-like ligule at the base of the leaf blade.

A community of cheatgrass stems; it is not uncommon for some of the foliage to turn yellow prematurely, especially during dry times.

The leaf blade emerges from the sheath, which reaches up from the base of the plant.

Immature, non-reproductive cheatgrass foliage; the foliage is soft and palatable, and no florets have emerged.

detailed leaf info

Cheatgrass has a fibrous root system. It does not spread from these roots, but the root systems of individual plants are often linked together by adventitious roots, as pictured here.

detailed root info

Closeup image of cheatgrass seeds; they are a common contaminant found in crop seed throughout the United States.

detailed fruit / seeds info

Seasonal Life Cycle

– Seeds typically germinate in early fall when moisture increases, and grow rapidly until temperatures drop

– While aboveground growth is limited in the winter, root development continues even through near-freezing soil temperatures; by spring, its root system is almost fully developed and has effectively gained control of the site

– Once temperatures begin warming up in late winter or early spring, cheatgrass develops rapidly; within 2 to 3 months, it may already have flowered, gone to seed, and fully dried up. You will notice the once soft and green florets are now purple to brown, dry and pokey

– Usually flowers in spring; seeds shatter within a week of reaching maturity; plants die and dry up soon after

3. Infestation Basics

“Cheatgrass was accidentally introduced early in the twentieth century and became a wandering waif along unpaved roads snaking through an ocean of silver gray sagebrush.”

– James Young, Cheatgrass: Fire and Forage

Where does it grow and how does it spread?

Spread of cheatgrass at its core, is facilitated by the displacement of native grasses due to both human and natural disturbance.

“Disturbances” are events which destroy existing vegetation, such as a fire or flood, leaving behind bare soil. These openings in the soil create opportunities for new plants to come in, but many plants have a difficult time growing shortly after a disturbance event. Cheatgrass is a so-called “pioneer species”, which are plants that are adapted to thrive specifically under disturbed soils.

While cheatgrass can thrive in almost any disturbed environment, it is a much more aggressive invader on drier sites, which will be further explained below. Not only that, but its seeds are adapted to be carried by the upwards drafts created by fire, making burned sites particularly susceptible to cheatgrass invasions.

Key takeaway: The consistent presence of an abundant community of native or desirable plants will help keep this pernicious invader at bay.

Why is it so invasive?

Under the soil, cheatgrass continues to grow roots through the winter, effectively depleting the site’s water and nutrients by the time spring rolls around.

Cheatgrass is a winter annual; it grows quickly through the cool months and then blooms and dies early in the spring.

As discussed, cheatgrass is a pioneer species, which means it excels at quickly consuming whatever available nutrients exist around it. This is not a huge problem where there are abundant resources; even with cheatgrass’ aggressive resource hoarding, there will still be enough to support a variety of other plants along with it.

Arid environments are characterized by low resource availability (water, soil carbon, and other nutrients). Despite these tough conditions, natural desert ecosystems are home to thousands of unique plants and animals which are uniquely adapted to live within the boundaries of the desert. Here, where water and nutrients exist under a delicate balance, cheatgrass goes from a nuisance to an ecological disaster.

When cheatgrass enters a dry site, it progressively starves out native vegetation, using each yearly cycle to grow its footprint and take up more and more of the scarcely available water. This transition is accelerated by fire, which cheatgrass invites all summer long with its dry, dead foliage. The landscape, as USDA researcher and native seed expert James Young describes, “has begun a transition through black ash to golden brown annual grass as [its dominant aspect]”.

Common risk factors for invasion

- Human activity: removal of existing vegetation for development, resource extraction, or other human activities creates an opening for cheatgrass seeds to germinate and begin invading. Additionally, cheatgrass seeds to hitchhike onto disturbed sites on heavy machinery, tools & equipment, and even the clothing of workers.

- This risk can be reduced by properly cleaning heavy machinery and equipment, and by revegetating with competitive plants following the disturbance.

- Overgrazing: When livestock are allowed to graze in a single area for too long, they will rip through the existing vegetation and expose the top layer of soil. This creates an opening for cheatgrass seeds, but this risk can be mitigated by practices that move cattle around more frequently such as rotational grazing.

- Proximity to burned areas: Cheatgrass seeds have evolved to take advantage of intense wildfire activity. They disperse their seeds through the high winds created by large fires, which allows them to travel to neighboring sites. Additionally, when fires get so big and hot that they kill off the top layer of soil as well as the pre-existing vegetation, it creates the perfect opening for cheatgrass (and not much else) to take hold.

- Site dryness: As discussed, cheatgrass spreads much more easily on drought-prone sites.

Impacts

Here is a short summary of the worst effects of allowing cheatgrass to spread unabated throughout our landscape.

Fire Hazard |

As a winter annual, cheatgrass dies off early in the year, leaving dry dead vegetation that starts and carries fires easily. These fires work to its advantage, creating the disturbances necessary to expand its footprint. Fire becomes more likely as cheatgrass spreads; “Successive fires become common, and each fire reduces the surviving shrub cover and native seed bank” (USFS Fire Effects |

Reduces biodiversity |

Cheatgrass is a winter annual, which means its primary growth happens in the winter when there’s very little competition from other plants. In the early spring when cheatgrass is mature, its stands have claimed a significant portion of the resources in the area, severely reducing the amount of moisture, nutrients and space available for any other plants. In this way, cheatgrass effectively suppresses any other vegetation in the areas in which it is allowed to grow. Many of the ecosystems invaded by cheatgrass are severly damaged and can no longer support a native plant community; where cheatgrass has taken over, it is likely to remain the dominant species; according to the Forest Service, cheatgrass can come to dominate an area within the first or second year following vegetation disturbance, and can remain dominant there for 40 to 80 years (USFS Fire Effects). |

Toxic to horses and livestock |

Animals can graze on cheatgrass early in the year when the vegetation is still green and soft. However, it dies early in the growing season, and the dried up florets become tough and spikey, potentially injuring or rupturing animals’ digestive organs |

4. Management Strategies

Managing a cheatgrass infestation can be challenging. Here is a short summary of how to think about this challenge and the most important things to keep in mind.

DO’s

- Integrate a variety of management strategies; this is not a “one-and-done” weed!

- Focus on preventing the formation and spread of seed

- Mow within a week of flowering to reduce seed production

DON’Ts

- Wait until the problem is out of control – prevention and early detection are key

- Assume that a single herbicide application or burn treatment will fix the issue

- Ignore the plant’s life cycle; timing of treatment must be matched to the specific life cycle of cheatgrass (see Phenology)

Quick summary of managing cheatgrass using non-chemical methods

Hand-pulling |

Individual plants or small patches can be pulled by hand or hoed in early spring before seeds are ripe. |

Mowing |

Mowing is not usually recommended, but can reduce seed production if conducted shortly after flower initiation and before seeds mature. Plants cut earlier will regrow. Plants should be mowed to about 2 inches with the bolting stems removed. Repeated mowing (every 3 weeks) can eliminate seed production in areas where herbicide applications are unacceptable. |

Cultivation |

Shallow cultivation shortly after the main flush of germination and again a little later can eliminate most seedlings. In agricultural fields, tilling soil with a method that deeply buries seeds in fall or early spring can help control bromes. In the Great Basin, tillage to establish summer fallows is a useful method of suppressing bromes and allowing establishment of perennial grasses. |

Grazing |

|

There are no established biocontrol agents for the weedy bromes. Several soil fungi have been tested for their suppressive effect on downy brome. None have proven effective.

- CHEMICAL

- Growth Regulators

- Lipid Synthesis Inhibitors

- Aromatic Aminoacid Inhibitors

- Branched Chain Aminoacid Inhibitors

- Photosynthetic Inhibitors

From UC Davis:

“The following specific use information is based on published papers and reports by researchers and land managers. Other trade names may be available, and other compounds also are labeled for this weed. Directions for use may vary between brands; see label before use. Herbicides are listed by mode of action and then alphabetically. The order of herbicide listing is not reflective of the order of efficacy or preference.”

Although they do not generally kill annual grasses, many of the growth regulator herbicides, particularly aminopyralid and picloram, have been shown to reduce seed production in downy brome. In addition, aminopyralid and aminocyclopyrachlor have been shown in some studies to provide good preemergence control of downy brome at higher rates.

Clethodim

|

|

Fluazifop

|

|

Glyphosate

|

|

Imazapic

|

|

Imazapyr

|

|

Propoxycarbazone-sodium

|

|

Rimsulfuron

|

|

Sulfometuron

|

|

Sulfometuron + chlorsulfuron

|

|

Sulfosulfuron

|

|

Hexazinone

|

|

5. Gallery

NMSU’s Extension Weed Specialist Dr. Leslie Beck on Cheatgrass

This video is specific to cheatgrass in Taos County and was the result of a collaboration between Taos Soil & Water Conservation District and New Mexico State University.

6. References & Further Reading

References

- DiTomaso, J.M., et al. (2013). Ripgut, red, and downy brome (cheatgrass). Weed Control in Natural Areas in the Western United States. Weed Research and Information Center, University of California. Retrieved from wric.ucdavis.edu/information/natural%20areas/wr_B/Bromus_diandrus-madritensis-tectorum.pdf

- Whitson, T.D., et al. (2006). Bromus tectorum. Weeds of the West (9th ed., p. 431) Western Society of Weed Science.

- Young, J. A. and Clements, C. D. (2009). Cheatgrass: Fire and Forage. University of Nevada Press.

- Zouhar, K. (2003). Bromus tectorum. In: Fire Effects Information System [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory. Retrieved from www.fs.usda.gov/database/feis/plants/graminoid/brotec/all.html

Further Reading

- Author’s Last Name, Initial(s). (Year, Month Day of publication). Title of work. Website. https://URL

- Author’s Last Name, Initial(s). (Year, Month Day of publication). Title of work. Website. https://URL

Photo (c) Chris Evans, University of Illinois, Bugwood.org

Did you know?

Nec litora facilisi quisque nunc egestas enim curabitur molestie nam dictumst metus cum donec nascetur.

Photo (c) Fred Fishel, University of Missouri, Bugwood.org

Photo (c) Bruce Bosley, Colorado State University, Bugwood.org

Did you know?

Nec litora facilisi quisque nunc egestas enim curabitur molestie nam dictumst metus cum donec nascetur.

Photo (c) Tom Heutte, USDA Forest Service, Bugwood.org