Cheatgrass

Bromus tectorum

Class

This plant is widespread across our state and is designated as a Class C Noxious Weed by the New Mexico Department of Agriculture.

Read more >>>

Hazard

This plant is documented to negatively impact fire regimes in our region. Its presence can increase the frequency and/or severity of fires.

Read more >>>

Toxic

This plant has been documented to sicken or injure horses.

Read more >>>

QUICK FACTS

- Cheatgrass (or downy brome) is a non-native grass that displaces native plants and severely degrades New Mexico’s unique ecosystems. It is especially invasive in arid range lands and is credited with the mass destruction of native sagebrush prairie throughout the Western United States.

- This plant gets its competitive advantage from its winter-annual life cycle. It germinates through the cold season, taking up all the soil nutrients and snow-melt… making it extremely difficult for other plants to germinate in the spring.

- Cheatgrass also dies very early in the year; it is usually dead by the summer and fall, leaving behind highly flammable tinder during the hottest part of the year. Across the landscape, cheatgrass has severely worsened and intensified fire regimes.

- Animals can graze on cheatgrass early in the year when the vegetation is still green and soft. However, it dies early in the growing season, and the dried up florets become tough and spiky, potentially injuring or even rupturing the digestive organs of horses and livestock.

1. Overview

Across the western United States, this prolific grass has earned the nickname “cheatgrass” among farmers and ranchers for its impressive ability to “cheat” them out of profits.

If you live in the western US, you are as familiar with cheatgrass as you are with the hassle of picking out their sharp, barbed seeds from your clothes and your dog’s fur. Bromus tectorum, commonly named downy brome around the world, is one of the most important crop pests for land managers in the country. Since the early 1800’s cheatgrass has contributed to the degradation of our rangelands, as well as exacerbated fire regimes throughout the west.

History of Cheatgrass

Cheatgrass is native to the Eurasian steppe. It is thought to have traveled in the shadow of herders in those regions, traveling from central Asia and across the Mediterranean. Since then it has traveled all around the globe as a contaminant of crop seeds. In the United States it was first identified in the 1860’s, and today it occurs throughout most of the North American continent, from Greenland to northern Mexico.

It has been particularly destructive in the Great Basin and Inter-mountain West, which span multiple states, from western Oregon on down to New Mexico. Its seeds stowed away within shipments of legitimate crop seed, and it snuck its way across the range until overgrazing allowed it to dominate.

In the early 19th century, when ranchers began introducing their livestock to the western rangelands, they quickly realized that irrigable land and water here was too scarce to grow the hay meadows necessary to support cattle through the winter. So they turned them out onto the open land, where their cows feasted on wild rose, willow thickets, and even went to town on the sagebrush. Ranchers relied particularly on native bunchgrasses to fill the hay gap during the winter months, but found that those too were becoming more scarce year after year. In their place, a “mystery” grass began showing up, by the roadside, under the sagebrush, and it provided forage for cattle just when the ranchers needed it most. Cheatgrass grew in the aftermath of the destruction of native vegetation, and at first the ranchers welcomed it, and even sought to plant it themselves. But before they got the chance, they found it had already sprung up spontaneously everywhere they looked.

According to the Forest Service, cheatgrass infestations in these regions have increased dramatically over the last 20 years, with some sources indicating over 100 million acres infested and millions of dollars in lost profits. Today, cheatgrass is responsible for human and environmental harm, from the decimation of sagebrush ecosystems, to devastating grassland fires.

2. ID Guide

What does it look like?

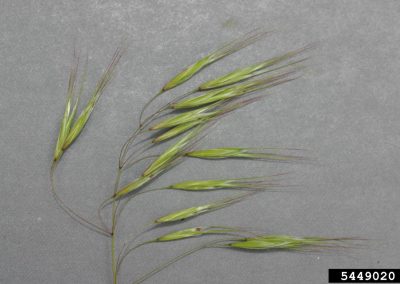

Grasses can be typically difficult to tell apart from each other, especially when in their early stages of growth. Cheatgrass can be distinguished, even in its early stages by particularly hairy leaf blades and sheaths. The most common lookalike is Japanese brome (Bromus japonicus) which can exist in the same areas as cheatgrass, but usually prefers wetter soils. The two grasses are easier to identify when older, as cheatgrass will have a drooping panicle with long, straight awns, while the awns of Japanese brome are twisted. Having trouble identifying a weed? Contact us.

Key Features

- Plant: Cheatgrass is a tufted bunchgrass, appearing as solitary bunches or more often as a patch. Individual plants usually grow about 4 to 30 inches tall. When the plants are young, the foliage is soft and green. As cheatgrass matures, the foliage and especially the seed heads become purplish, and later reddish-brown as it dries up. By the time the plant dies, the foliage is brown or tan and the texture becomes very dry, coarse, and spiky.

- Leaves: are flat blades with a sheath surrounding the stems; both the leaf and the sheath are densely covered with thin hairs. The base of the leaf blade has a short “collar” – a short translucent membrane of thin hairs called a ligule.

- Flowers: While grasses do not have obvious flowers, you will notice the florets, or flowering tops of cheatgrass are dense and slender. They are arranged in a loose, branching cluster of seedheads called a panicle. These seedheads are about 3-6 inches long and have a characteristic drooping behavior, often found nodding along with the breeze.

- Seeds: Each awn is attached to a brown, hairy seed which is narrow and about 1/2 inch long .

cheatgrass-florets2

Young cheatgrass florets; at this point they may be safe and palatable for livestock.

cheatgrass-deadflorets

Fully dead cheatgrass florets can injure the throats and digestive tracts of animals

cheatgrass-dryfloret

Dead cheatgrass turns fully brown or tan; the florets are now very dry and spikey. At this point, it can injure livestock and horses if consumed.

cheatgrass-stem

Cheatgrass stems begin to turn red as the plant matures, note the thin white collar-like ligule at the base of the leaf blade.

cheatgrass-stems

A community of cheatgrass stems; it is not uncommon for some of the foliage to turn yellow prematurely, especially during dry times.

3. Infestation Basics

“Cheatgrass was accidentally introduced early in the twentieth century and became a wandering waif along unpaved roads snaking through an ocean of silver gray sagebrush.”

– James Young, Cheatgrass: Fire and Forage

Where does it grow and how does it spread?

Spread of cheatgrass, at its core, is facilitated by the displacement of native grasses due to both human and natural disturbance.

“Disturbances” are events which destroy existing vegetation, such as a fire or flood, leaving behind bare soil. These openings in the soil create opportunities for new plants to come in, but many plants have a difficult time growing shortly after a disturbance event. Cheatgrass is a so-called “pioneer species”, which are plants that are adapted to thrive specifically under disturbed soils.

While cheatgrass can thrive in almost any disturbed environment, it is a much more aggressive invader on drier sites, which will be further explained below. Not only that, but its seeds are adapted to be carried by the upwards drafts created by fire, making burned sites particularly susceptible to cheatgrass invasions.

Key takeaway: The consistent presence of an abundant community of native or desirable plants will help keep this pernicious invader at bay.

Why is it so invasive?

Under the soil, cheatgrass continues to grow roots through the winter, effectively depleting the site’s water and nutrients by the time spring rolls around.

Cheatgrass is a winter annual; it grows quickly through the cool months and then blooms and dies early in the spring.

As discussed, cheatgrass is a pioneer species, which means it excels at quickly consuming whatever available nutrients exist around it. This is not a huge problem where there are abundant resources; even with cheatgrass’ aggressive resource hoarding, there will still be enough to support a variety of other plants along with it.

Arid environments are characterized by low resource availability (water, soil carbon, and other nutrients). Despite these tough conditions, natural desert ecosystems are home to thousands of unique plants and animals which are uniquely adapted to live within the boundaries of the desert. Here, where water and nutrients exist under a delicate balance, cheatgrass goes from a nuisance to an ecological disaster.

When cheatgrass enters a dry site, it progressively starves out native vegetation, using each yearly cycle to grow its footprint and take up more and more of the scarcely available water. This transition is accelerated by fire, which cheatgrass invites all summer long with its dry, dead foliage. The landscape, as USDA researcher and native seed expert James Young describes, “has begun a transition through black ash to golden brown annual grass as [its dominant aspect]”.

Common risk factors for invasion

- Human activity: removal of existing vegetation for development, resource extraction, or other human activities creates an opening for cheatgrass seeds to germinate and begin invading. Additionally, cheatgrass seeds to hitchhike onto disturbed sites on heavy machinery, tools & equipment, and even the clothing of workers.

- This risk can be reduced by properly cleaning heavy machinery and equipment, and by revegetating with competitive plants following the disturbance.

- Overgrazing: When livestock are allowed to graze in a single area for too long, they will rip through the existing vegetation and expose the top layer of soil. This creates an opening for cheatgrass seeds, but this risk can be mitigated by practices that move cattle around more frequently such as rotational grazing.

- Proximity to burned areas: Cheatgrass seeds have evolved to take advantage of intense wildfire activity. They disperse their seeds through the high winds created by large fires, which allows them to travel to neighboring sites. Additionally, when fires get so big and hot that they kill off the top layer of soil as well as the pre-existing vegetation, it creates the perfect opening for cheatgrass (and not much else) to take hold.

- Site dryness: As discussed, cheatgrass spreads much more easily on drought-prone sites.

Impacts

Fire Hazard

As discussed, cheatgrass dies off early in the year, leaving a cover of dry dead vegetation throughout the hot summer months. The dry foliage easily catches fire, and fire becomes more likely as cheatgrass spreads; “Successive fires become common, and each fire reduces the surviving shrub cover and native seed bank” (USFS Fire Effects). A large infestation can start severe fires, with repeating rounds of fire every 3 to 5 years. If that doesn’t sound frequent, consider that the sagebrush rangelands which cheatgrass thrives in evolved with significant fires occurring only every 32 to 70 years (Pellant, 1989).

Aside from killing off competing vegetation around it, these fires can also spread to neighboring ecosystems, paving the way for further cheatgrass infestations. Cheatgrass seeds are lightweight and fire-adapted, allowing them to be carried by the upwards drafts of wildfires.

Loss of Biodiversity

We’ve discussed the relationship between fire and cheatgrass expansion. We’ve also seen how, as a winter annual, its growth cycle is timed to effectively use up the site’s water and nutrients before other plants even have the chance to come up in the spring.

The problems don’t end there. Aside from serving as fire kindling, a field covered by dead, yellow cheatgrass also prevents other plants from establishing throughout the year. A dense infestation can result in soils covered by mats of dry yellow, preserving the area for the next generation of cheatgrass. When native vegetation is absent, the site becomes unattractive to pollinators and wildlife. Over time, the ecosystem transitions into one dominated by cheatgrass and fire, with little appeal for wildlife.

Ecosystems that host cheatgrass invasions are severely damaged and can no longer support a native plant community. According to the Forest Service, cheatgrass is quick to dominate a new area (sometimes within a year or two after the initial vegetation disturbance), and once established, can remain dominant there for 40 to 80 years (USFS Fire Effects).

Restoration efforts become more difficult the longer cheatgrass remains dominant on a site, as the native seed bank within the soil is depleted and replaced by seeds of cheatgrass.

Agriculture and Food Security

Cheatgrass is as much of a threat to native ecosystems as it is to agricultural landscapes. In fact, agricultural fields are potentially at higher risk of invasion. Agricultural machinery and equipment are common vectors of cheatgrass seeds, and the frequent soil disturbance characteristic of most agricultral landscapes creates many easy openings for invasion.

Agricultural crops face an uphill battle to compete for resources against cheatgrass. In a series of studies, researchers compared the growth of cheatgrass to common agricultural wheatgrasses within the same time frame. Not only did cheatgrass produce nearly double the amount of roots that the wheatgrasses did, but its presence actually reduced the growth of the wheatgrass seedlings (Pellant, 1996). Cheatgrass is also a prolific seed producer in the early part of the growing season, making it difficult to keep at bay once introduced.

Cheatgrass degrades the quality of the land, which lowers crop yield and quality, and ultimately results in a loss of land value for the operator. When it comes to livestock, it offers poor quality forage for a very short period of time, and is no forage at all for the much greater time it remains dead on the field. The USDA reports that around 50 million acres of grazing lands in the West alone are estimated to have a cover of more than 15% cheatgrass. Fighting cheatgrass is a key aspect of protecting our food security and preserving the economic value of our rural working landscapes.

Horses and Livestock Injuries

Today, cheatgrass continues to be a valuable source of forage early in the year. Sheep, goats, horses, and cattle all readily graze on cheatgrass when its foliage is soft and green. Targeted livestock grazing can be used to reduce the size infestations; some land managers even advocate for the use of grazing of the dry brush to reduce wildfire fuels in the summer (See Management Strategies > Non-Chemical > Cultural). However, it’s important to consider the nutritional value and potential risks associated with cheatgrass consumption by livestock.

- Potential injuries: Foraging on dry cheatgrass exposes livestock and horses to potential injuries to their eyes, flesh, or damage to their fleece. As the plant matures, its awns become tough and spikey, potentially leaving open wounds on animals.

- Infections: The awns can get lodged into an animal’s muzzle and gums, resulting in cysts and inflammation. When the awns penetrate as far as the jawbone, it can cause “lumpy jaw”, a severe infection that produces permanent hard swellings on the jaw bones of cattle.

- Cheatgrass seedheads sometimes harbor ergot, a poisonous fungus that causes ergotism in livestock. Ergotism constricts the host’s blood vessels, resulting in lameness, dry gangrene, and loss of limbs. Even without these symptoms present, ergotism can impair milk production and reproduction. Wet conditions when cheatgrass is flowering encourage the growth of this pathogen.

- Inadequate forage: It loses its nutritional value as it loses its green and dries up; mature cheatgrass does not provide enough protein to adequately support nutrition. Livestock that graze on mature cheatgrass will need to have their diets supplemented for sufficient protein.

4. Management Strategies

Managing a cheatgrass infestation can be challenging. Here is a short summary of how to think about this challenge and the most important things to keep in mind.

DO’s

- Integrate a variety of management strategies; this is not a “one-and-done” weed!

- Focus on preventing the formation and spread of seed

- Mow within a week of flowering to reduce seed production

DON’Ts

- Wait until the problem is out of control – prevention and early detection are key

- Assume that a single herbicide application or burn treatment will fix the issue

- Ignore the plant’s life cycle; timing of treatment must be matched to the specific life cycle of cheatgrass

** The following information is provided courtesy of the UC Weed Research and Information Center. The Taos Soil and Water Conservation District does not endorse the use of any particular product, brand, or application thereof. **

Quick summary of managing cheatgrass using non-chemical methods

Hand-pulling |

Individual plants or small patches can be pulled by hand or hoed in early spring before seeds are ripe. |

Mowing |

Mowing is not usually recommended, but can reduce seed production if conducted shortly after flower initiation and before seeds mature. Plants cut earlier will regrow. Plants should be mowed to about 2 inches with the bolting stems removed. Repeated mowing (every 3 weeks) can eliminate seed production in areas where herbicide applications are unacceptable. |

Cultivation |

Shallow cultivation shortly after the main flush of germination and again a little later can eliminate most seedlings. In agricultural fields, tilling soil with a method that deeply buries seeds in fall or early spring can help control bromes. In the Great Basin, tillage to establish summer fallows is a useful method of suppressing bromes and allowing establishment of perennial grasses. |

Grazing |

|

There are no established biocontrol agents for the weedy bromes. Several soil fungi have been tested for their suppressive effect on downy brome. None have proven effective.

- CHEMICAL

- Growth Regulators

- Lipid Synthesis Inhibitors

- Aromatic Aminoacid Inhibitors

- Branched Chain Aminoacid Inhibitors

- Photosynthetic Inhibitors

Information regarding chemical management strategies for this plant has been provided by the UC Weed Research and Information Center.

“The following specific use information is based on published papers and reports by researchers and land managers. Other trade names may be available, and other compounds also are labeled for this weed. Directions for use may vary between brands; see label before use. Herbicides are listed by mode of action and then alphabetically. The order of herbicide listing is not reflective of the order of efficacy or preference.”

Although they do not generally kill annual grasses, many of the growth regulator herbicides, particularly aminopyralid and picloram, have been shown to reduce seed production in downy brome. In addition, aminopyralid and aminocyclopyrachlor have been shown in some studies to provide good preemergence control of downy brome at higher rates.

Clethodim

|

|

Fluazifop

|

|

Glyphosate

|

|

Imazapic

|

|

Imazapyr

|

|

Propoxycarbazone-sodium

|

|

Rimsulfuron

|

|

Sulfometuron

|

|

Sulfometuron + chlorsulfuron

|

|

Sulfosulfuron

|

|

Hexazinone

|

|

5. Educational Video

NMSU’s Extension Weed Specialist Dr. Leslie Beck on Cheatgrass

This video is specific to cheatgrass in Taos County and was the result of a collaboration between Taos Soil & Water Conservation District and New Mexico State University.

6. References & Further Reading

References

- Baynes, M., et al. (2012). A novel plant–fungal mutualism associated with fire. Fungal Biology, 116(1), 133–144. doi.org/10.1016/j.funbio.2011.10.008

- DiTomaso, J.M., et al. (2013). Ripgut, red, and downy brome (cheatgrass). Weed Control in Natural Areas in the Western United States. Weed Research and Information Center, University of California. Retrieved from wric.ucdavis.edu/information/natural areas/wr_B/Bromus_diandrus-madritensis-tectorum.pdf

- Mosley, J. (2018). Targeted Livestock Grazing to Suppress Cheatgrass. Department of Snimal and Range Sciences, Montana State University. Retrieved from www.montana.edu/extension/sanders/Prescription for Cheatgrass November 25 2018.pdf

- Pellant, M. (1989). The cheatgrass wildfire cycle: are there any solutions?. Symposium on Cheatgrass Invasion, Shrub Die-Off, and Other Aspects of Shrub Biology and Management. Las Vegas, NV. Retrieved from www.fs.usda.gov/rm/pubs_int/int_gtr276/int_gtr276_011_018.pdf

- Randall, B. (2020). Don’t Get Cheated By Invasive Grasses. USDA NRCS Working Lands for Wildlife. www.farmers.gov/blog/dont-get-cheated-by-invasive-grasses

- Whitson, T.D., et al. (2006). Bromus tectorum. Weeds of the West (9th ed., p. 431) Western Society of Weed Science.

- Young, J. A. and Clements, C. D. (2009). Cheatgrass: Fire and Forage. University of Nevada Press.

- Zouhar, K. (2003). Bromus tectorum. In: Fire Effects Information System [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory. Retrieved from www.fs.usda.gov/database/feis/plants/graminoid/brotec/all.html

Photo (c) Chris Evans, University of Illinois, Bugwood.org

Did you know?

Cheatgrass is the main food source for the chukar, an exotic game bird of the pheasant family introduced by hunters in the 1930’s. A fellow native of Eurasia, the chukar is pre-adapted to thrive in degraded sagebrush ecosystems, and thrives in tandem with cheatgrass invasions of US rangelands. While chukar hunting continues to be a popular sport, the success of this species comes at the expense of the greater sage-grouse, a native turkey-like bird which depends on healthy sagebrush ecosystems for its survival.

Photo (c) Fred Fishel, University of Missouri, Bugwood.org

Photo (c) Bruce Bosley, Colorado State University, Bugwood.org

Did you know?

Fungus may be responsible for cheatgrass’ fire-resistance. Plants gain different traits depending on the soil organisms that live off of them. Recent studies have shown that when cheatgrass forms a symbiotic relationship with a fire-associated fungus (like morels!), it gains the very traits that make it more prone to starting fires and surviving them.

Photo (c) Tom Heutte, USDA Forest Service, Bugwood.org