Siberian Elm

Ulmus pumila

Class C Noxious Weed

This plant is widespread in the state and has been designated a Class C Noxious Weed by the New Mexico Department of Agriculture.

Read more >>>

Riparian Threat

This plant is known to invade riparian areas or otherwise damage the health and abundance of our water resources.

Read more >>>

QUICK FACTS

- Siberian elm is a hardy, fast-spreading weed commonly planted for its ability to tolerate marginal conditions and quick provision of shade.

- It is a drain on local water resources; it hogs available soil moisture for itself, but sweats it out profusely during high temperatures.

- Siberian elm contributes to loss of biodiversity, as it limits the amount of water available for other plants, resulting in an overall drier, harsher environment.

- The roots and limbs of this hardy tree are common causes of property and structural damage; its roots can crack pipes and concrete, and its decaying limbs can fall from 70+ feet in the air.

- Once established, it is very difficult to remove! Even after cutting it down, this tree can resprout from root suckers or from the cut stump itself.

1. Overview

Love it or hate it, this tree is everywhere! Once popular as a landscape and ornamental tree, the Siberian elm is now a controversial fixture across New Mexican towns.

Far from its start in our nation as a purported miracle tree, Siberian elm inspires a mix of frustration and reticent appreciation from most folks today. Aside from its detrimental effects on native ecosystems and water resources, in many areas it has become a nuisance due to its prolific seeding and aggressive spread. Even where it was intentionally planted, many homeowners today are saddled with the labor and costs of removing this tenacious tree.

History of Siberian Elm

- Originally from the Manchurian region, from eastern Russia down towards Korea. Its native landscape reminds us of the driest parts of our state.

- Introduced as ornamental in 1860s.

- Ecological similarities lead to its success in the the US, especially in the West, where it was able to exploit its niche without the mediating influences of its native environment

- Farmers planted as single-row windbreaks in 1960s in response to the Dust Bowl.

- Former New Mexico Gov. Clyde Tingley found a solution to the shadeless, drought-prone corridors of his city in a Mongolian plant. Native to the Gobi Desert, it could thrive even when water was scarce.

- The Governor handed out the wrinkled, dime-sized seeds of Siberian elm trees to anyone who would plant them.

- This echoes a pattern of settlers coming to the west, promising to “green up the place” and giving away fast-growing plants like the Siberian elm to the populace.

- This trend continues in the early days of the railroad, with the advent of nurseries as a new vector of distribution. The siberian elm was treated as a panacea to address what the people at the time perceived as the problems inherent in the western landscape. [Old timey adverts Chinese elm-miracle tree!]

- They grew fast and hardily, and by the 1970s, the trees had spread throughout the state.

- How and when was ecological damage recognized? When and how did it become a problem for people?

2. Identification

What does it look like?

Siberian elm is often mis-identified as “Chinese elm”, though these are different plants; Siberian elm’s is dark and furrowed, while Chinese elm has a smooth, splotchy bark. It’s also possible to mistake the young seedlings for our native alders (Alnus spp.); note that the Siberian elm’s leaves are always strictly alternate (see below), while alders are more unevenly arranged. Having trouble identifying a weed? Contact us.

Key Features

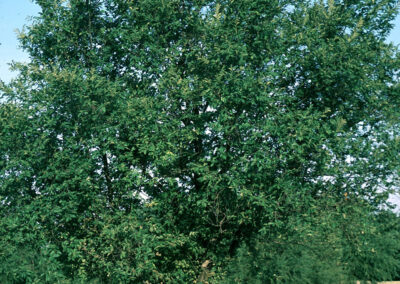

- Tree or shrub – given the opportunity, it can grow up to 70ft tall

- Highly branching with an open crown; branches grow upwards, and are flexible but brittle and may easily break off as the tree ages; usually a build-up of leaves and woody debris can be found under mature Siberian elms

- Leaves: alternate on the branch, almond-shaped and tapered into a point at the end; leaf margins are mildly serrated or toothed

-

- Deciduous: the foliage changes color with the seasons, from green in the spring to yellow in the fall, and then shedding them entirely in the winter cold. Brown leaves are also possible, a sign of elm beetle infestation

-

- The tree is monoecious, which means each individual produces both seeds and pollen.

-

- Flowers: tiny and inconspicuous, showing up as small reddish-brown clusters of 3-15 flowers on the previous year’s new branches.

- Seeds: Papery, flat, light green to yellow in color; main seed is encased in between translucent “wings” called samara

-

siberianelm-seeds

Siberian elm seeds are flat, small, and round- or oval-shaped; the main seed is surrounded by a thin papery wing, slightly translucent and light green to yellow or tan; distinctive brown tip

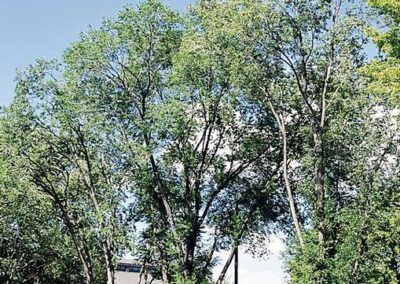

siberianelm-mature

Mature Siberian elms grow up to 70ft tall and are commonly planted as shade trees in urban settings.

siberianelm-bark

The bark of Siberian elm is dark grey, deeply grooved with a rough texture, especially as it ages. Younger trees may have a more uniform texture composed of interlocking narrow plates.

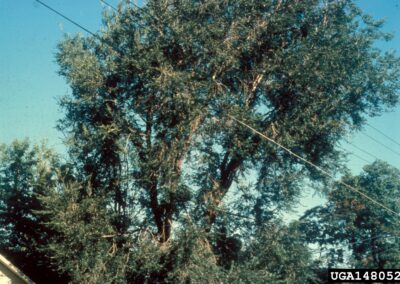

siberianelm-hazard

This Siberian elm growing into power infrastructure creates an electrical hazard if the branches were to collapse or catch fire

siberianelm-leaves

The leaves grow in alternate arrangement, they are egg-shaped but end in a lance-tip. Margins serrated, with light-colored veins

siberianelm-developing

Siberian elm blossoms, once pollinated, develop into the winged seeds characteristic of the tree

siberianelm-dryseed

Siberian elm seeds germinate quickly in favorable conditions, but are otherwise short-lived and will dry up and lose viability if they aren’t able to germinate

siberianelm-seedclusters

Once pollinated in the spring, the inconspicuous flower clusters give way to the papery Siberian elm seeds we are so familiar with. They develop on the branch and await to be dispersed by wind or rain.

siberianelm-foliageseeds

Siberian elm is known for releasing prolific amounts of papery seed pods, which can become a nuisance in the urban settling

3. Infestation Basics

“Nulla gravida orci a odio. Nullam varius, turpis et commodo pharetra, est eros bibendum elit, nec luctus magna felis sollicitudin mauris. Integer in mauris eu nibh euismod gravida.”

– Name, Source

Why is it so invasive?

Nulla gravida orci a odio. Nullam varius, turpis et commodo pharetra, est eros bibendum elit, nec luctus magna felis sollicitudin mauris. Integer in mauris eu nibh euismod gravida.

Duis ac tellus et risus vulputate vehicula. Donec lobortis risus a elit. Etiam tempor. Ut ullamcorper, ligula eu tempor congue, eros est euismod turpis, id tincidunt sapien risus a quam. Maecenas fermentum consequat mi.

Donec fermentum. Pellentesque malesuada nulla a mi. Duis sapien sem, aliquet nec, commodo eget, consequat quis, neque. Aliquam faucibus, elit ut dictum aliquet, felis nisl adipiscing sapien, sed malesuada diam lacus eget erat. Cras mollis scelerisque nunc. Nullam arcu. Aliquam consequat.

Key takeaway: Sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat.

Where does it grow and how does it spread?

Nulla gravida orci a odio. Nullam varius, turpis et commodo pharetra, est eros bibendum elit, nec luctus magna felis sollicitudin mauris. Integer in mauris eu nibh euismod gravida.

Duis ac tellus et risus vulputate vehicula. Donec lobortis risus a elit. Etiam tempor. Ut ullamcorper, ligula eu tempor congue, eros est euismod turpis, id tincidunt sapien risus a quam. Maecenas fermentum consequat mi.

Donec fermentum. Pellentesque malesuada nulla a mi. Duis sapien sem, aliquet nec, commodo eget, consequat quis, neque. Aliquam faucibus, elit ut dictum aliquet, felis nisl adipiscing sapien, sed malesuada diam lacus eget erat. Cras mollis scelerisque nunc. Nullam arcu. Aliquam consequat.

Key takeaway: Sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat.

Common risk factors for invasion

- Human activity: Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Praesent venenatis metus at tortor pulvinar varius. Nulla facilisi. Sed dignissim lacinia nunc. Curabitur tortor. Pellentesque nibh. Aenean quam. In scelerisque sem at dolor. Maecenas mattis. Sed convallis tristique sem. Proin ut ligula vel nunc egestas porttitor. Morbi lectus risus, iaculis vel, suscipit quis, luctus non, massa. Fusce ac turpis quis ligula lacinia aliquet.

- This risk can be reduced by properly cleaning heavy machinery and equipment, and by revegetating with competitive plants following the disturbance.

- Areas of neglect: Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Praesent venenatis metus at tortor pulvinar varius. Nulla facilisi. Sed dignissim lacinia nunc. Curabitur tortor. Pellentesque nibh. Aenean quam. In scelerisque sem at dolor. Maecenas mattis. Sed convallis tristique sem. Proin ut ligula vel nunc egestas porttitor. Morbi lectus risus, iaculis vel, suscipit quis, luctus non, massa. Fusce ac turpis quis ligula lacinia aliquet.

- This risk can be mitigated by practices that move cattle around more frequently such as rotational grazing.

- Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Praesent venenatis metus at tortor pulvinar varius. Nulla facilisi. Sed dignissim lacinia nunc. Curabitur tortor. Pellentesque nibh. Aenean quam. In scelerisque sem at dolor. Maecenas mattis. Sed convallis tristique sem. Proin ut ligula vel nunc egestas porttitor. Morbi lectus risus, iaculis vel, suscipit quis, luctus non, massa. Fusce ac turpis quis ligula lacinia aliquet.

- Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Praesent venenatis metus at tortor pulvinar varius. Nulla facilisi. Sed dignissim lacinia nunc. Curabitur tortor. Pellentesque nibh. Aenean quam. In scelerisque sem at dolor. Maecenas mattis. Sed convallis tristique sem. Proin ut ligula vel nunc egestas porttitor. Morbi lectus risus, iaculis vel, suscipit quis, luctus non, massa. Fusce ac turpis quis ligula lacinia aliquet.

Impacts

Water Resources

Those of us who live in dry and desert areas understand the paramount importance of water: how we use it and how we share it determines how much will be available to go around. This is even more true when it comes to plants, and in this regard, Siberian elm is a bad neighbor: greedy and wasteful.

Most plants have evolved to close their leaves’ “pores” (called stomata) in response to drought conditions as a means to conserve water Siberian elm has developed a different adaptation not to conserve water, but to keep cool in the heat: it sweats! That’s right, when exposed to drought, instead of closing up its pores, Siberian elm actually releases more water from its leaves as evaporation – all while continuing to pull more water from the surrounding areas.

Compared to other trees, Siberian elm has a very shallow, but wide-spreading root system. While most tree roots grow deep so as to penetrate and recharge the aquifer beneath, Siberian elm concentrates its roots along the first 1-3 feet of soil. This is the depth at which most understory plants like grasses and flowers are able to grow, and so they are significantly disadvantaged when they grow near a Siberian elm; as the elm grows, its roots can rapidly displace nearby vegetation, and make it harder for new plants to reach enough space, moisture, nutrients for its own roots.

For a desert plant, Siberian elm is a prolific water user, in part due to the inefficiency with which it utilizes available moisture. What its root system lacks in depth, it more than makes up for in spread, with water uptake occurring well beyond the tree’s canopy. In many cases, a Siberian elm planted in one property will affect water availability and plant growth in the adjacent properties as well, with root systems spreading to a length equivalent to four times its height! [cite]

Infrastructure Issues

Despite their many issues, Siberian elms are still beloved for the visual appeal and shade they provide to otherwise barren areas, and as such are ubiquitous in New Mexico’s urban and even rural landscapes. Back in the day, Siberian elms were planted indiscriminately, resulting in some very unfortunate placements. The trees tend to quickly outgrow their surroundings, with little regard for whatever else happens to be nearby.

Arborists will often describe trees like the Siberian elm as a from of job security, as homeowners across the state struggle with the issues that come with harboring these trees. The roots and branches of this tree are very tough; they do not struggle to break through even concrete and pavement if given enough time. They are known to grow through sewage pipes, and to crack through even asphalt roads and paved sidewalks!

Mature Siberian elms in particular can become a hazard as they continue to grow, impacting infrastructure such as power lines, sewage and water pipes, etc. The tree routinely sheds off sections of its canopy that aren’t getting access to sunlight anymore; the branches are heavy but the wood itself is quite brittle, causing large branches to snap off quite easily. Falling from trees up to 70 ft in height, they can do quite a lot of damage to whatever is around.

It is unfortunate that many Siberian elms are planted right next to residential structures, power lines, and other critical infrastructure. The damage can be quite expensive to fix, as the tree is tenacious and may be difficult to eradicate.

Public Health

Everyone who lives in the vicinity of these trees is familiar with the copious piles of seeds they produce every year. Another unwelcome sign of this tree’s reproductive cycle is the pollen, which is responsible for many unpleasant symptoms in the spring and summer. Some folks are particularly sensitive to elms.

4. Management Strategies

Controlling Siberian elm spread is best accomplished when the trees are not yet sprouted or still in the seedling stage and can still be pulled by hand. Once established, removal becomes progressively more difficult with age. For best success, clean up the seeds, and pull those that germinate while they are still young.

DO’s

- nunc ipsum est, aliquam eleifend est eu, luctus porttitor turpis

- nam sed odio commodo, viverra lectus at, eleifend ex

- risus a mattis efficitur, orci sapien lobortis est, eget elementum nisl nibh consectetur nisl

DON’Ts

- nunc ipsum est, aliquam eleifend est eu, luctus porttitor turpis

- nam sed odio commodo, viverra lectus at, eleifend ex

- risus a mattis efficitur, orci sapien lobortis est, eget elementum nisl nibh consectetur nisl

** The following information is provided courtesy of the UC Weed Research and Information Center. The Taos Soil and Water Conservation District does not endorse the use of any particular product, brand, or application thereof. **

Quick summary of managing Siberian Elm using non-chemical methods.

Mowing |

Add Content |

Tilling/Hand-pulling, etc |

Add Content |

Grazing |

Add Content |

Prescribed burns |

Add Content |

Please be aware: biocontrol agents are living organisms; they do not differentiate between different types of thistles. Some of these biocontrol agents can go on to become invasive species in their own right as they form outbreaks within crucial native thistles.

Ceutorhynchus litura

|

Add Content |

Larinus planus |

Add Content |

Urophora cardui |

Add Content |

Puccinia punctiformis |

Add Content |

Information regarding chemical management strategies for this plant has been provided by the UC Weed Research and Information Center.

“The following specific use information is based on published papers and reports by researchers and land managers. Other trade names may be available, and other compounds also are labeled for this weed. Directions for use may vary between brands; see label before use. Herbicides are listed by mode of action and then alphabetically. The order of herbicide listing is not reflective of the order of efficacy or preference.”

2,4-D

|

|

Aminocyclopyrachlor +

|

|

Aminopyralid

|

|

Clopyralid

|

|

Dicamba

|

|

Picloram

|

|

Glyphosate

|

|

Chlorsulfuron

|

|

Imazapyr

|

The herbicide label indicates that 4 to 6 pt product/acre gives some level of control, but imazapyr is not usually the herbicide of choice for the control of Canada thistle. |

Sulfometuron

|

|

5. Educational Video

NMSU’s Extension Weed Specialist Dr. Leslie Beck & ISA Certified Arborist Ben Wright on Siberian elm

This video is specific to Siberian elm in Taos County and was the result of a collaboration between Taos Soil & Water Conservation District and New Mexico State University. Special thanks to Ben Wright, vice-chair of the Taos Tree Board, for contributing his expertise on the topic as a featured guest.

6. References & Further Reading

References

- Name. (year). Title. Publisher, vol(ch), pp. https://url

Further Reading

- Author’s Last Name, Initial(s). (Year, Month Day of publication). Title of work. Website. https://URL

- Author’s Last Name, Initial(s). (Year, Month Day of publication). Title of work. Website. https://URL

Photo (c) Tom DeGomez, University of Arizona, Bugwood.org

Did you know?

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Morbi lacinia molestie dui. Praesent blandit dolor. Sed non quam. In vel mi sit amet augue congue elementum. Morbi in ipsum sit amet pede facilisis laoreet. Donec lacus nunc, viverra nec, blandit vel, egestas et, augue. Vestibulum tincidunt malesuada tellus. Ut ultrices ultrices enim.

Photo (c) blaze708, via iNaturalist

Photo (c) jacob_whit via iNaturalist

Did you know?

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Morbi lacinia molestie dui. Praesent blandit dolor. Sed non quam. In vel mi sit amet augue congue elementum. Morbi in ipsum sit amet pede facilisis laoreet. Donec lacus nunc, viverra nec, blandit vel, egestas et, augue. Vestibulum tincidunt malesuada tellus. Ut ultrices ultrices enim.

Photo (c) k11ra, via iNaturalist